On the impossibly cold morning of August 8, 1929, Sergeant C. Trundle, an Inspector for the Great Slave Lake Region of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, reported a grisly scene inside a rundown cabin on the banks of the Thelon River in the Northwest Territories. Trundle's affidavit describes the discovery of the skeletal remains of three explorers, all Englishmen. One skeleton was that of John Hornby, whose unpublished manuscript, In The Land of Feast and famine by J. Hornby, or a Life in the Arctic Region, was found alongside his body. Hornby was a seasoned explorer who frequented the Thelon area. Wanting to attract attention to the unspoiled natural beauty of the Thelon River, Hornby embarked on another expedition in early 1927, hoping to prove that he could live in the desolate, wilderness of the area subsisting only on Caribou meat and whatever other game he could procure. Hornby starved to death on April 14, 1927. Next to Hornby's corpse, Sergeant Trundle found the body of Harold Allard, who died only a couple of weeks later, on May 4 1927. The third set of remains belonged to Edgar Christian, a 19-year old amateur explorer.

On the impossibly cold morning of August 8, 1929, Sergeant C. Trundle, an Inspector for the Great Slave Lake Region of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, reported a grisly scene inside a rundown cabin on the banks of the Thelon River in the Northwest Territories. Trundle's affidavit describes the discovery of the skeletal remains of three explorers, all Englishmen. One skeleton was that of John Hornby, whose unpublished manuscript, In The Land of Feast and famine by J. Hornby, or a Life in the Arctic Region, was found alongside his body. Hornby was a seasoned explorer who frequented the Thelon area. Wanting to attract attention to the unspoiled natural beauty of the Thelon River, Hornby embarked on another expedition in early 1927, hoping to prove that he could live in the desolate, wilderness of the area subsisting only on Caribou meat and whatever other game he could procure. Hornby starved to death on April 14, 1927. Next to Hornby's corpse, Sergeant Trundle found the body of Harold Allard, who died only a couple of weeks later, on May 4 1927. The third set of remains belonged to Edgar Christian, a 19-year old amateur explorer.When RCMP scouts first discovered the old hut by the Thelon, at first they did not notice the bodies. They entered in and noticed a handwritten note affixed to the stove, with four words written in a desperate, almost childish scrawl:

Who ... Look ... In ... Stove

Inside the stove was Edgar Christian's logbook, which presented a day-to-day account of the deadly winter of 1927. There have been different accounts of the story, all suggesting a tragic scene. On the morning of June 1, 1927, Edgar Christian finished his last diary entry, and placed it alongside a note to his mother and father in the ashes of the stove. After writing the note asking whoever discovered their remains to look inside the stove, he crawled inside his red Hudson Bay's blanket and died. Edgar Christian's last diary entry is cryptic, yet somewhat telling:

9 a.m. Weaker than ever. Have eaten all I can. Have food on hand but heart peatering? Sunshine is bright now. See if that does any good to me if I get out and bring in wood to make fire.

Make preparations now.Got out, too weak and all in now. Left things late.

Christian began writing these daily entries in October 1926, before he embarked on the trek with Hornby and Allard. His clipped, pithy style is matter-of-fact, as if he were protecting future readers from the grisly details of starvation. Death was a lonely and personal business, and he only wanted to present a bare minimum of details. Christian also depicts the barren, frozen steppes of the upper Northwest Territories, where gale-force winds and winter temperatures averaging somewhere south of -20 degrees Fahrenheit made exploration a hazardous business indeed. The Thelon River area that Hornby, Allard, and Christian explored in 1926 and 1927 was then terra incognita. Hornby made regular visits to the area, and his growing love for the fecund yet bare Thelon area no doubt inspired Allard and Christian to go along on this last, deadly jaunt.

One morning, almost 50 years later, a group of American and Canadian campers were pitching tents at Warden's Grove, near the Thelon River. Newspaper accounts indicate that Gary Anderson, 30, of Rock Island, Ill.; Chris Norment, 26, of Las Vegas; Kurt Mitchell, 28, of Jackson, Wyo.; John Mordhorst, 28, of Rock Island; Michael Mobley, 26, of Mesa, Ariz., and Robert Common, 33, of St. Anne de Bellevue, Canada were keen outdoorsmen, sharing John Hornby's love for the Thelon wilderness, and recreating the explorer's last, and most famous expedition.

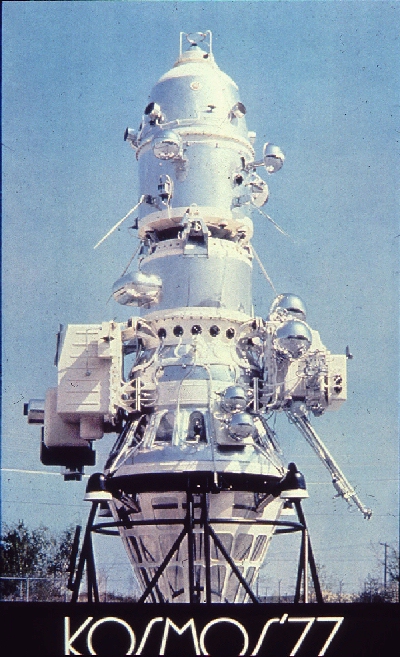

On the morning of January 24, 1978, one of these men noticed a white blazing object streaking across the sky, spewing fiery bits in its wake. Mobley and Mordhorst ventured to the impact site, and on the way, noticed smoldering pieces of metal wreckage. These, however, were actually parts of wreckage from COSMOS 954, a Soviet Radar Ocean Reconnaissance Satellite (RORSAT). COSMOS 954

had a relatively short life span. Launched on September 18, 1977 from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhistan, COSMOS 954 featured the latest in Soviet nuclear reactor technology: a Romashka-type reactor carrying a Uranium-235 core. The satellite was designed to monitor naval activity in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, and in January 1978, reports began to surface that COSMOS 954's orbit was beginning to decay. And to make matters worse, the Soviet Space Agency was unable to jettison the satellite's reactor core due to a mechanical malfunction.

had a relatively short life span. Launched on September 18, 1977 from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhistan, COSMOS 954 featured the latest in Soviet nuclear reactor technology: a Romashka-type reactor carrying a Uranium-235 core. The satellite was designed to monitor naval activity in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, and in January 1978, reports began to surface that COSMOS 954's orbit was beginning to decay. And to make matters worse, the Soviet Space Agency was unable to jettison the satellite's reactor core due to a mechanical malfunction.During a brief diplomatic spat between the U.S. and Soviet governments, it had been generally accepted that COSMOS 954 would reenter the Earth's atmosphere with it reactor core. This would be an unprecedented type of nuclear disaster -- an airborne, upper-atmospheric release of radioactive debris. There was even speculation that the satellite would crash in India. But it wasn't until January 24th that anyone had any inclination as to where COSMOS 954 would crash. Early that morning, the satellite entered the Earth's atmosphere somewhere over the Queen Charlotte Islands (north of Vancouver), and tumbled in a northeastern direction across Great Slave Lake, Fort Resolution, Yellowknife, Fort Reliance, and fin

ally towards Baker Lake.

ally towards Baker Lake.After the Soviet government admitted that COSMOS 954 indeed had a nuclear reactor on board, a cleanup operation was commenced by the U.S. and Canadian. Dubbed Operation Morning Light, the cleanup effort not only involved the on-site recovery of radioactive debris, but also utilized spectrometer-equipped Royal Canadian Air Force as well as high-altitude missions by U2 spyplanes.

The clean up effort ended in April 1978. By that time, crews assigned to Operation Morning Light surveyed over 124,000 square kilometers and logged over 4500 hours of flying time, all in search for pieces of the doomed COSMOS 954. In the end, it was determined that the Romashka reactor and its contents burned up in the atmosphere, and that the pieces strewn along the hoarfrost posed very little danger. The most radiologically intense piece, about the size of a nickel, was found on February 23 and appropriately sent to the Whiteshell Nuclear Research Establishment in Pinawa, Manitoba.

What strikes me as interesting about these two narratives is how they both end in the same location. Also, the very first piece of wreckage found by the American and Canadian campers in 1978, with two bent metal rods splaying out in opposite directions, even looked like a pair of Caribou antlers that John Hornsby would have loved to have seen in the deadly winter of 1927-1928. The newspaper accounts even describe them as "antlers." And finally, the satellite crash, how it must have looked like a falling star on that cold January morning, and the terrible, sad ending to Edgar Christian's Thelon adventure ... it reminds me of the last lines of W.H. Auden's "Musee des Beaux Arts"(1940):

In Brueghel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

No comments:

Post a Comment